SOURCE:

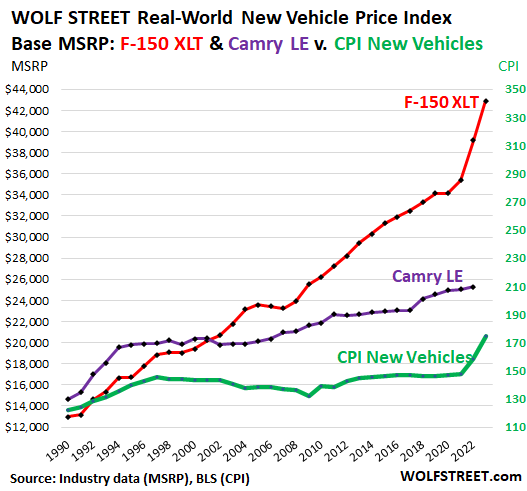

But Toyota barely raised the price of the Camry. Here are 32 years of real-world price increases compared to the CPI for New Vehicles.

It’s the time of the year again when I get to update the extra-special proprietary non-adjusted WOLF STREET Real-World New-Vehicle Price Index, or more precisely the F-150 XLT and Camry LE Price Index, with the MSRPs of the 2023 model year.

The F-150 XLT is just above the XL model (low end of the F-series). High-end models of the F-series can cost over twice as much as an XLT. The Camry LE turned into the low end of the Camry line when the Camry L was discontinued. The F-150 XLT and the Camry LE both go back to 1990 and beyond, and both are bestsellers, which is why I use them for my index.

I use the base version of these models, with no add-ons and without destination and delivery charges, to show the price increases of the bestselling truck and the best-selling car in the US going back to 1990. And for an extra-special hoot, I compare that to the CPI for new vehicles.

The chart below shows the MSRP for each model year of the F-150 XLT (red, left scale), and the Camry LE (purple, left scale), and the Consumer Price Index for New Vehicles (green, right scale). We’ll get to the details and numbers in a moment:

Since 1990:

- MSRP of F-150 XLT: +231%

- MSRP of Camry LE: +77%

- CPI for new vehicles: +43%, including the 18% increase over the past 24 months.

The price increase of the 2023 F-150 XLT blew my ears off, compared to the 2022 model and the 2021 model, about +10% each year, two years back-to-back, total blowout price spikes. Over those two model years, from the 2021 model to the 2023 model, the base MSRP without destination and delivery charges jumped by $7,540, or by 21%, from $35,400 for a 2021 model to $42,940 for the 2023 model. Time to go on a buyers’ strike, no?

This is what the inflationary mindset is all about: Manufacturers think that people will pay whatever because people paid whatever plus big-fat addendum stickers last year, so here we go.

Ford has been whining all year about its cost increases, and used this whining as reason to jack up its retail pricing – the inflationary mindset at the manufacturer. A lot of media attention was focused on the multiple price jack-ups of the electric F-150 Lightning. But not much ink was spilled on the blowout price jack-ups for the second year in a row for the regular F-150 XLT – the truck that the average American is supposed to be able to buy.

By contrast, Toyota raised the 2023 Camry LE price by a benign 2.6% to $25,945 without destination and delivery charges, after having raised it only 1% in the prior year.

Trucks are just so profitable for dealers and automakers. The thing is – automakers figured this out long ago – Americans don’t mind paying out of their nose for big equipment while letting automakers and dealers pocket huge profit margins.

But when it comes to a car, suddenly, they’re very price conscious and they don’t want anyone to make any profits. This has been the case for 20 years. And that’s why the MSRP of the Camry, which until the year 2000 had been above that of the F-150 XLT, is now 40% below it!

Last year at this time, it was a huge mess. Supply chain chaos had tangled up production plans, and the ramp-up of production of the 2022 models was delayed. The whole thing was utter chaos. I delayed my update until November 20, and even then, I could only get the F-150 XLT rumor-price that was floating around among dealers, and that an exasperated dealer passed on to me, which turned out to be way low.

At the time, dealers were slapping big-fat addendum stickers on the few 2021 trucks that had, and MSRPs were suddenly no longer the top price, but the bottom price. I’d never seen anything this crazy in my entire life. Why were dealers able to do that? Because they could, because people were paying whatever, because the inflationary mindset had taken over.

This year, the chaos has settled down somewhat. The obnoxious addendum stickers are largely gone. Some 2023 Camrys are arriving at dealers. The first 2023 F-150 models may be arriving in November.

The CPI for new vehicles jumped by 10% year-over-year through August, and +7.3% in the prior 12-month period, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, having finally picked up some of the price increases. But these increases in the CPI were from a low base that hadn’t really moved up at all for 20 years – due to the “hedonic quality adjustments.”

Hedonic quality adjustments make sense on a conceptual basis. If you compare a current model-year F-150 to the 1990 model-year F-150, you see that they’re the same vehicles in name only. The new model is bigger and more powerful (the base engine is a 290 hp 3.3L V6 with a silky-smooth electronic 10-speed automatic transmission). It has better fuel economy (EPA rates the 2022 model at 19 mpg in the city and at 24 mpg on the highway) and comes with all kinds of safety features, including four-wheel-disc brakes (as opposed to drum brakes in the rear), plus antilock braking, multiple airbags, and all kinds of passive safety systems. The new model is loaded with convenience features (note the 8-inch “Productivity Screen” in the instrument cluster among many other features). It has 17-inch aluminum wheels, and a gazillion other things that buyers of the 1990 model couldn’t even dream off.

The CPI for new vehicles attempts to calculate the price changes of the same product over time. If the product is improved in dramatic ways, as vehicles are, then the CPI estimates the costs of those improvements every year and removes them from the index. My gut tells me that these “hedonic quality adjustments,” though they make sense on a conceptual basis, have been exaggerated.

The result is that the CPI new vehicles increased by only 21% since the year 2000, driven almost entirely by the 18% increase over the past two years. The last two years of the CPI make sense.

But it’s more complicated. The outcome is that CPI for new vehicles increased by 21% since 2000, while over the same period, the price of the basic Ford truck jumped by 121%, to $42,940 in 2023, from $19,410 in 2000.

Since 2000, “median family income” increased by 75%, according to the Census Bureau, from $50,732 in 2000 to $88,590 in 2021. This has the effect that these new trucks have moved out of reach for many more consumers.

On the other hand, the Camry, which has also gotten larger, more powerful, and better in myriad ways, has increased in price by “only” 27% since 2000 – and with median family income creasing by 75%, it has become more affordable. Its price increases since 2000 are not far above the new-vehicle CPI’s increase of 21%.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.